Action Against Ebola: Building Trust Through Collaboration in Guinea

Description

On February 14, 2021, an Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreak was declared in Guinea, following the confirmation of 3 cases in the region of Nzérékoré. As a trade center that shares borders with Cote d’Ivoire, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, an outbreak in this region was of particular concern. This was the first outbreak in Guinea since the 2013-2016 outbreak, which claimed more than 2,500 lives. The World Health Organization (WHO), the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), and the United Nations International Emergency Children’s Fund (UNICEF) worked together on a community-level response for the treatment and prevention of EVD. With infrastructure in place from the COVID-19 response, the Collective Service for Risk Communication and Community Engagement (RCCE) at the global, regional, and country levels facilitated coordination between the three agencies and leveraged existing networks, resources, and information systems to help provide an innovative, community-centered approach to the outbreak.

Just four months later, the Ebola outbreak was declared over, with only 23 recorded cases and 12 deaths. The success of the response is a testament to the immense efforts made by the Guinean people, and the synergy of partners who together, provided collective knowledge, skills, and resources to prevent an epidemic.

“[During] the last Ebola outbreak, the partners worked in isolation, each with their own agenda. This time, the joint commission was much more organized and we were able to manage rumors and give accurate information, which made us more credible.” – Christophe Milimolo, Chair of radio network in Nzérékoré

RESPONSE

As a dedicated collaborative partnership put in place to fight the COVID-19 pandemic, the Collective Service and its core partners began facilitating coordination and gathering resources as soon as the EVD outbreak was declared. Global and regional staff of the Collective Service adapted information management tools for data collection and analysis and assisted with deployment at the country-level in order to share community feedback across the response. The RCCE coordination team at the regional level created a repository of tools, capacity building assets, policy documents and minimum actions built on experiences from the 2018 EVD outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo. These documents were made available to all partners engaged at the country level and promoted through dedicated coordination staff of the Collective Service who were able to nurture collaboration, facilitate connections, and enhance awareness of partner activities in order to avoid the duplications of efforts.

As part of the commitment to a consistent approach to community engagement, the Provincial Health Department along with UNICEF, WHO, IFRC, and the Guinea Red Cross, taught a comprehensive set of modules to train key actors and stakeholders on a range of topics including: epidemiology, transmission, vaccination, public health and safety measures (PHSM), how to communicate about the disease within Guinea’s cultural context, how to work with communities to increase buy-in, how to manage resistance, and how to use media to create awareness and dispel myths. Each of the agencies brought forward their expertise to provide comprehensive training to members of the Response Commission, and the RCCE coordination team was consistently available to support complimentary partnerships.

“During the last epidemic some team members were killed by furious populations. The joint training on reluctance and the sub-commission [on reluctance prevention and management] helped us to manage resistance by combining efforts. We utilized mobile radio and the community feedback mechanism to reach out and exchange with communities to overcome resistance” — Diaoune Mamadou, locally elected municipal official

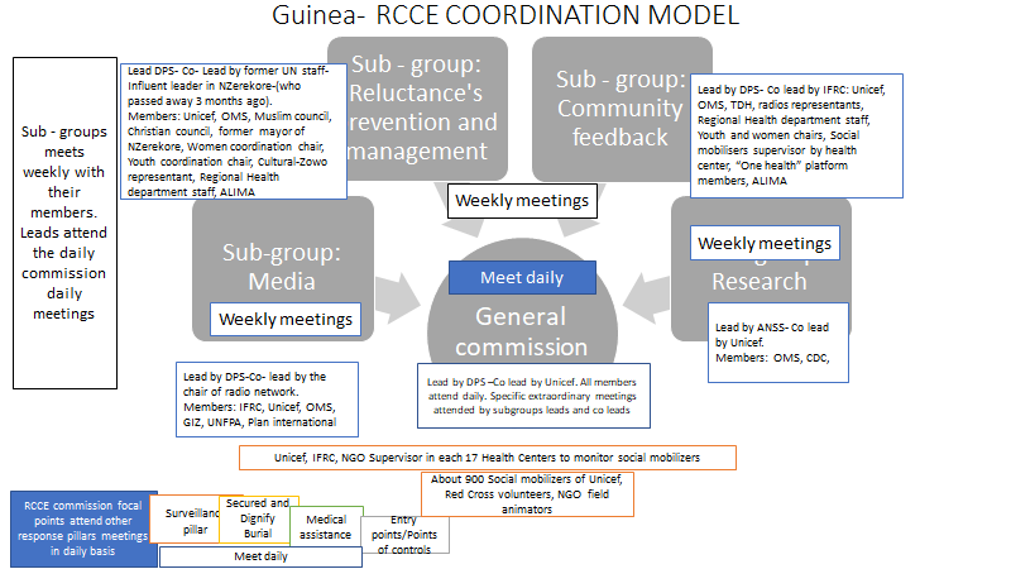

Following the joint training, a General RCCE Commission and several focused sub-commissions were formed, matching key actors to different aspects of the response. The General RCCE Commission was composed of the Prefecture Department of Health (DPS), the Collective Service core agencies and dedicated interagency coordinator, international NGOs, local NGOs, local elected actors, faith-based organizations, women and youth organizations, traditional-influential leaders (Zowos), radio producers, journalists, and social media influencers.

The General RCCE Commission met daily to discuss updates on the evolution of the response’s activities including logistics, next steps, challenges, community feedback, data collected through social mobilisers, and reports from the sub-commissions. RCCE sub-commissions, composed according to key actor profiles and interests, met weekly and focused on reluctance prevention and management, community feedback, media, and social science research. Focal points in RCCE also attended the daily meetings of the other pillars of the response: surveillance, safe and dignified burial, medical assistance, and control points. Information collected from the other pillars was then integrated in the action plan. Finally, social mobilizers went door-to-door over the course of the response to speak with community members, gather feedback and insights, listen to questions and concerns, ad document rumors and myths. They also supported community action, referred ill community members to health centers, and spoke to community members who had a deceased loved one about testing for EVD, as well as safe and dignified burial. These social mobilizers consisted of community members engaged in the training, in consultation with the RCCE General Commission

This coordination model allowed agencies and partners to deliberate on the response and then speak with one voice to communities. Communities could also respond to just one voice, avoiding confusion and chaos on the ground. RCCE was integrated into each of the response pillars, and with the help of the RCCE coordination team, a community feedback mechanism was put in place to create a direct line for communities (via conversations with social mobilizers and others) to express needs, fears, and expectations.

SPOTLIGHT

The first cases of EVD in Guinea were confirmed in Pagalay. In this village, female traditional healers play a special and powerful role in village decisions, particularly when it comes to preparation and burial of the dead. It was therefore particularly important to engage the community in a way that honored their role. UNICEF, IFRC, the Guinea Red Cross and WHO worked together to engage and empower the local healers and created a series of community conversations that enhanced transparency and presented the response as a unified effort.

Each of the proposed activities were acted out so that the village could provide feedback about any changes that were unacceptable, and also, to familiarize themselves with what would happen in the coming months. A mock burial was carried out in full view of community members, along with presentations on testing for EVD, vaccination, and what it would look like to talk to social mobilizers if a death in the family took place. These conversations were well received and the village leader publicly signed a written agreement to cooperate with the Response.

The conversations proved to be extremely fruitful in Pagalay, and village members began to take ownership of the effort to eliminate EVD in their village. People were able to receive medical care with either a suspected or confirmed case of EVD. One man who tested negative for EVD was able to receive medical care for a different ailment, which became a source of great praise toward the Response. By enrolling community members and attending to their needs, the Response was able to correct misunderstandings and Pagalay became a nationwide model for excellent EVD response at the community level.

CHALLENGES

Suspicions and notions of conspiracy were a major obstacle to the response. Vaccines, masks, and medical care were all claimed to be ways to contract EVD, rather than to prevent or treat it. Socio-economic disparity between response personnel and communities created misunderstandings and fueled accusations of ulterior motives. In one community, where cars were rarely seen, the sudden influx of visitors by car was obvious proof to the community that EVD was a hoax, designed to use the community to make money. There was also wide speculation that medical staff were harvesting organs from EVD patients for the black market.

Challenges also differed across generational lines. With greater access to disinformation coming from the internet, younger people tended to push back more on information coming from social mobilizers. Sometimes the spread or lack of spread of the disease did not fit within the typical epidemiological model. In instances where a confirmed death from EVD did not spread to close family members, it confirmed conspiracy theories that the EVD outbreak was not real.

LESSONS LEARNED

| LESSON | EXAMPLE(S) FROM GUINEA |

|

After social mobilizers were recruited for the response, it was discovered that many of them did not belong to the communities where they worked, or they were the local medical chiefs in the area. Acting on complaints from the community, the Response replaced the social mobilizers with local members of the community and the communities noticed. The trust built from responding appropriately to this request increased compliance and cooperation with Response teams. |

|

In the village where the first cases of EVD were reported, female traditional healers were traditionally responsible for preparation and burial. An anthropologist was able to facilitate discussions with local women to increase cooperation with the Response’s implementation of secure and dignified burial. |

|

In communities where certain organizations were not as well-known, local trusted organizations and volunteers were able to facilitate introductions and build trust for all emergency partners. |

|

In one community, where cars were rarely seen, the sudden influx of visitors by car was obvious proof to the community that Ebola was a hoax, designed only to use the community to make money. Once this issue was identified, response personnel made a concerted effort to carpool and limit the number of vehicles brought into the area. |

|

Organization of the joint training allowed each agency to offer their expertise to the response and ensure that all relevant topics were covered. Key actors who participated in the training therefore harmonized their approach and spoke with one voice, providing information and messages that were disseminated through various communication channels (NGOs, religious leaders, radio, etc.). |

|

Visual representations of activities that would take place were acted out for communities. This reduced shock/anger, and overall resistance to the Response. |

|

Faith leaders, local municipal leaders, radio producers, NGO, and CSO staff were all included in the general commission and sub-commissions. This allowed everyone to leverage their skills, networks, and resources to get harmonized, accurate messages to affected communities. |

|

In previous EVD outbreaks, communities were not always engaged in ways that empowered community members, and some violence occurred. Bringing community engagement to the forefront reduced community resistance and paved the way for other pillars of the response to operate smoothly. |

|

Deploying mobile radio stations in the affected areas strengthened trust in messages disseminated by familiar, local actors. The radio stations also allowed communities to be able to talk to each other through live broadcasts, provide feedback on specific messages, and promote good examples and practices of community members. |

|

Systematic information sharing among response staff provided critical insights to deal with community resistance. Given the security threats during the previous outbreak, this had the effect of building confidence among Response staff that they had the right information to work with communities. At the same time, Response staff were able to respond quickly to suspected cases. |

NEXT STEPS

“As an Imam, I benefited greatly from the training on how to prepare dignified burial[s] for people who died from Ebola. I want to expand this training to mosques across Guinea.” — Amadou Soumaoro, President of Muslim Council

The Collective Service at the global, regional, and country levels will continue to maintain its networks and partners to be able to respond to emerging issues in Guinea and elsewhere, such as EVD outbreaks. Lessons learned from the experience in Guinea will be added to the legacy documents and tools from the 2018 EVD outbreak in Democratic Republic of Congo as a resource that can be quickly adapted to future emergencies. The community feedback mechanism, an immense effort of the partners engaged in the Collective Service and the dedicated Information Management team, is currently being expanded across Western and Central Africa and Eastern and Southern Africa as an up-to-date monitoring tool to complement surveillance, and to keep a pulse on community perceptions that impact public health. In Guinea, with the network of trained professionals from the joint training, public health messages and community engagement interventions continue for COVID-19 along with preparedness activities for other potential emergencies.

The success in Guinea is proof that having ready, dedicated RCCE coordination and information management staff, along with a systematic approach to RCCE coordination at all levels, is critical to disease prevention and management. Prioritizing communication and coordination across partners and agencies, the Collective Service will continue to promote expert-driven, localized RCCE support to governments and partners in order to reduce redundancies, save partners resources and time, and ultimately save lives.

Additional languages

DETAILS

Organisation

Emergency

Region

Keywords